Cotton is everywhere in Uzbekistan. In plates, teapots, teacups, and ikat clothing. Why?

It traces back to the country’s extensive history of forced labor in the cotton-picking industry.

In November 2021, my mother and I visited the News of Central Asia exhibition at the NYC Jewelry Library curated by Aida Sulova, which showcased jewelry and cultural pieces from post-soviet countries of Central Asia such as Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan, along with a backstory of its significance. These pieces represented the political and historical background of each country.

When we reached the art piece depicting Uzbekistan, my mother started to cry. I realized that her emotional reaction was from Dilyara Kaipova’s artwork, “The Curse of Cotton.”

Cotton (or “paxta” in Uzbek) is notorious in Uzbekistan. The design is commonly seen in houseware items. Nevertheless, it was worked for through forced labor during the Soviet Union period, unlike today.

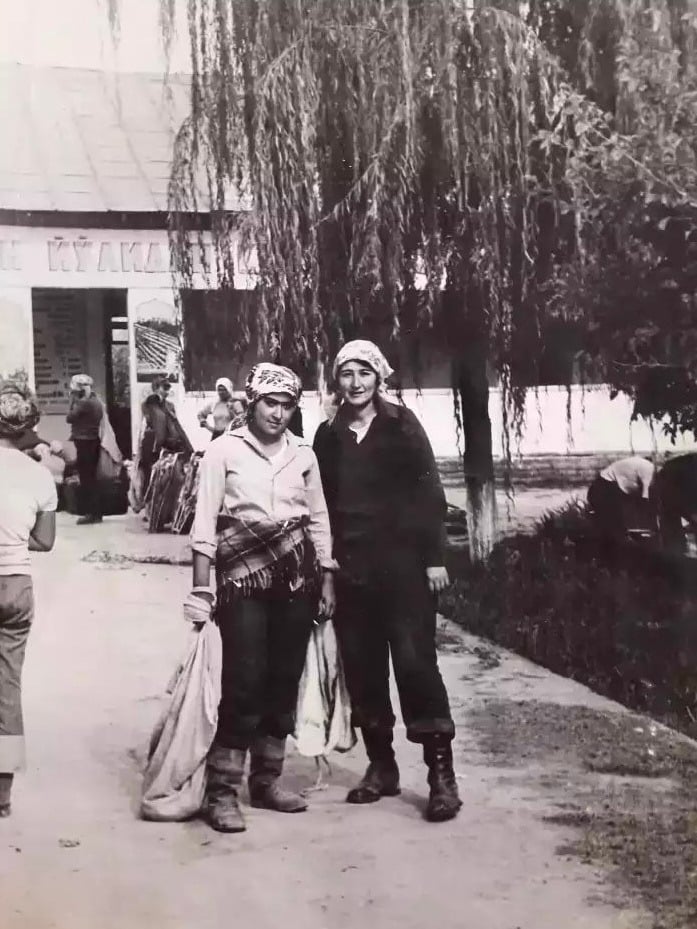

In Uzbekistan, cotton is ready by late August. By September, students from the 3rd grade to college are sent to pick cotton by their schools. Additionally, adults also engage in cotton picking as part of their employment.

Uzbekistan, also known as the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic at the time, was ranked top tier in cotton picking. Cotton picking was one of the ways that helped keep the economy stable during the Soviet Union. During the cotton harvesting season, all of Uzbekistan would be in a frenzy as the daunting task of picking 6 million tons of cotton by January loomed ahead. If successful, the message would spread through television and radio mediums.

Students would arrive home before the new year, but until then, they had to sleep in crowded quarters with thirty to forty individuals of the same gender. Their meal breaks were restricted to just thirty to forty-five minutes, during which they were served bread, tea, and macaroni soup. Hours were long, spanning a 12-hour interval from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m.

High school students, being minors, stayed for half the months that college students stayed in the field, and their hours were not as long. Similarly, elementary school students also had relatively shorter work hours, and they were allowed to return home once their hours were completed.

During their shift, college and high school students were required to pick 100 kilograms (220 pounds) of cotton. While elementary school students were permitted to pick 5 kilograms (11 pounds) of cotton.

Cotton picking would commence no matter the weather conditions. If it was windy, raining, or snowing, cotton was always picked. As a result of the harsh weather conditions and long hours, students’ hands would become bruised, blistered, and bloody.

High school and college students received a stipend. However, failing to harvest an acceptable amount of cotton would result in an insufficient stipend. If college and high school students were caught taking an unauthorized break or refused to pick cotton, they would face expulsion from school and loss of stipend.

Cotton has a deep-rooted and dark history in Uzbekistan. It’s evident from my mother’s emotional reaction to Kaipova’s artwork. Though a vital contributor to the nation’s economy during the communist regime of the Soviet Union, known for its motto, “Workers of the world, unite!” Once the Soviet Union fell, so did the forced labor of cotton picking. Nowadays, cotton picking is undertaken by those seeking employment and is voluntary.